I Created a 'Memento Mori' Still Life as a Philosophical Exercise

And I think you might like to try it too!

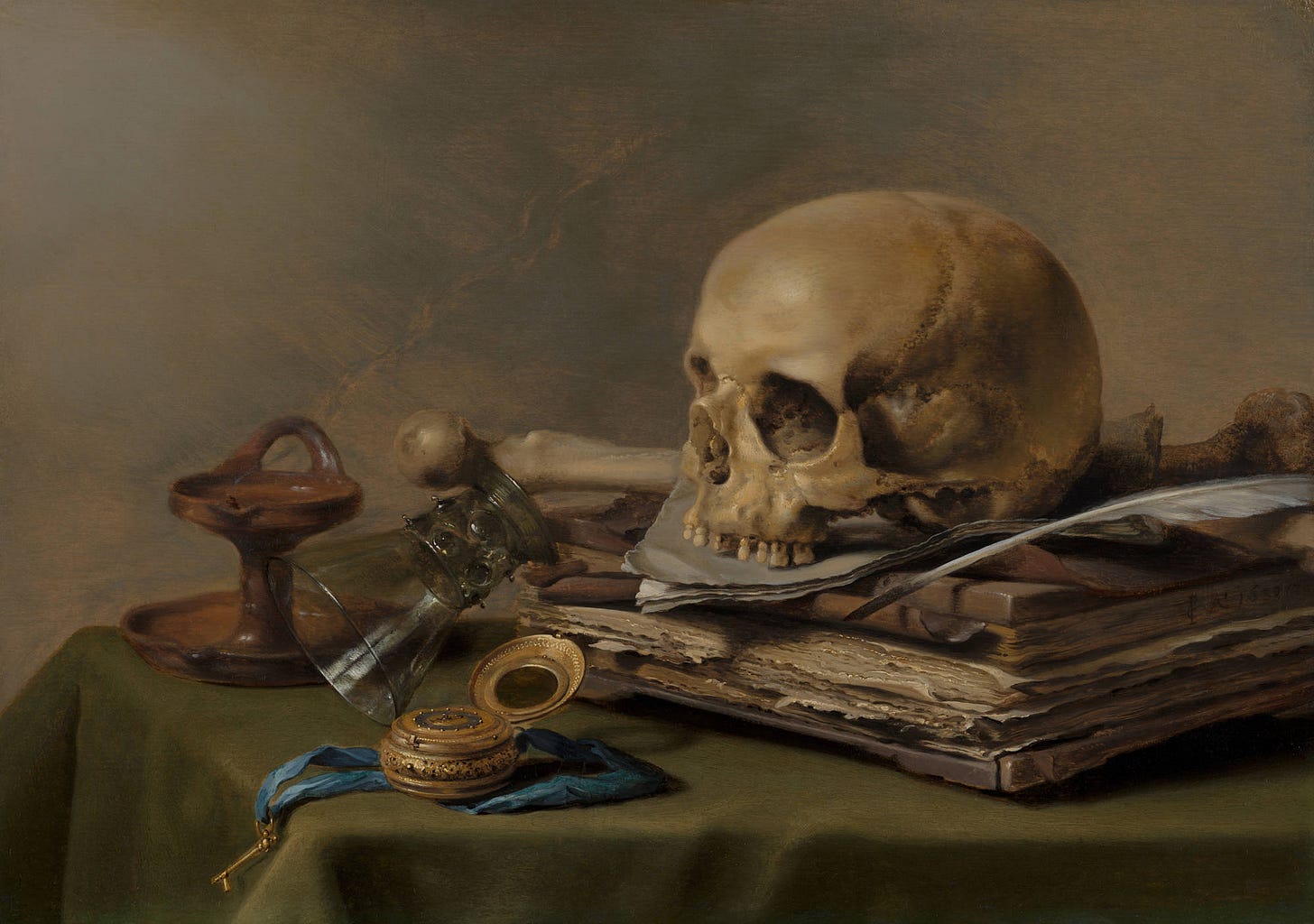

Following the 7 Days of Joyful Death Writing, I felt inspired to make some space in my cottage for a visual meditation on mortality and the impermanence of life. Drawing on the tradition of 16th- and 17th-century vanitas paintings, I curated my own memento mori still life, and I invite you to create one too.

Dear You —

Found around my cottage are objects that symbolise death and transience:

Wilting baby pink peonies on my white kitchen table.

An old pocket watch on the window sill in the living room.

A skull-shaped candle placed on a stack of Nick Cave books.

Half-burnt dinner candles on the shelf above the fireplace.

An ornamental pomegranate on a pile of books in a corner reading nook.

A photograph of my deceased grandmother, Calliope, taken on a balcony in Northern Greece when I was thirteen.

A worn and heavily annotated copy of Marcus Aurelius’s Meditations.

These objects, individually, all serve to remind me that life is transient and that I will die. They are memento moris1, but because they are randomly placed around the cottage, I often do not notice them.

What if I brought a selection of them together and, with purposeful consideration, arranged them as a still life in the style of Dutch vanitas paintings? What might happen if I literally cleared some space in my home to set the stage for death? What might the experience be like? What will it clarify for me? This week, I was excited to consider these questions.

A brief introduction to vanitas or memento mori paintings

Vanitas refers to works of art that depict objects symbolising transience and the fleeting pleasures of earthly life. They are a type or genre of memento mori artworks that remind us of our own mortality. As such, they include objects such as skulls and extinguished candles. However, vanitas paintings also include other objects such as mirrors, coins, books, jewellery and musical instruments that remind us of the empty futility of seeking happiness in worldly pursuits and pleasures.

Although the vanitas tradition flourished in the Netherlands in the early 1600s, the very first vanitas artwork is considered to be a line engraving made by Venetian artist Jacopo de’ Barbari in around 15042.

What you see is this: A naked woman looking at her image in a mirror; a contemplation of the fleeting nature of youth, beauty and life itself, a reminder that she, too, will age, decay and die, a memento mori. The word vanity has its roots in the Latin vanus, meaning empty and void. The messages of vanitas artworks is that the pursuit of and pride in worldly gains and physical beauty is in vain, for we will all die.

The vanitas tradition has a fascinating socio-religious-cultural context, and I encourage you to go and explore, but for the purposes of this letter, I’ll consider some early examples, examine the typical elements in these paintings, report on how I created my own memento mori still life, and hopefully inspire you to try your own.

Research and inspiration

I began reading about the history of vanitas painting and looking through images online, noticing composition fundamentals and arrangement principles.

On the whole, these still lifes are generally dark artworks: dark backgrounds, dark shadows, dark, earthy surfaces and fabrics.

The dark colours set the scene for a dramatic encounter with the objects of impermanence and futility. They are striking and memorable. An important feature in a memento mori practice.

And, although these are literally morbid scenes, they don’t make me feel distressed or frightened. Instead, these scenes are mindfully arranged, muted and oddly calming. And I am happy to accept their invitation to observe and contemplate mortality.

I looked closer at a few most prominent examples.

I notice that the skull is a central focus, but it’s not always necessarily the centre of the still life arrangement. It’s the most direct statement of mortality but it also speaks in relation to the other objects.

The arrangement is sometimes cluttered. Some items are toppled over, like the glass in Claesz’s painting (#2, above). This creates stunning drama and movement!

I notice diagonal lines appearing in the arrangement of the objects as well as in the light reflecting on the wall in Steenwyck’s painting above (#3, above).

Objects are positioned in relationship with other objects possibly suggesting symbolic connections. For example, flowers shown in various stages of bloom and decay.

I make a list of all the elements I see in the examples online.

Symbolic elements in vanitas still lifes

Skulls or bones are reminders of physical death

Hourglasses or clocks symbolise the passing of time

Extinguished candles suggest the end and brevity of life

Decaying fruit or flowers are reminders of the fleeting nature of beauty and youth

Watches and old books reflect the impermanence of knowledge and achievements

Bubbles — my favourite element! — reflect life’s fragility

Coins or luxury items represent the empty vanity of worldly wealth and consumption

Mirrors symbolise vanity, self-absorption and self-knowledge

How I created my memento mori or vanitas still life

1. Philosophical reflection

I approached this as an active philosophical meditation. I spent time reflecting on mortality especially in light of having completed the 7 Day memento mori practice with you all. I approached this activity slowly over the course of a few days. I journalled. I made notes. I spent time looking closely at vanitas examples.

2. Collection and curation

Studying the examples of vanitas paintings, and the list of elements above, I began foraging in the cottage for appropriate objects. I had a sense that I wanted a modern and lighter feel but mostly a traditional layout. However, there are so many contemporary possibilities:

Digital devices suggesting impermanence of technology, distraction, avoidance

Medication bottles reminding us that we are still mortal despite medical advances

Personal achievements reminding us of the fleeting rewards and recognition of diplomas, trophies, awards

Family photographs reminding us of the deaths of previous generations

For even edgier inspiration, you may like to explore Picasso, the work of Damien Hirst here and here and Sam Taylor-Johnson’s videos on decay.

Here are the objects I chose.

The shell

I love this broken shell. I don’t know what it is about the shore here on Loch Ryan or how shells are crushed in the wild Scottish waters, but I rarely find a perfect shell in these parts. Shells are always broken here. In any case, a constant reminder of the beautiful fragility of life.

The watch

This watch once belonged to an ancestor whose name and identity I do not know. It was handed down from father to brother to uncle to nephew (maybe) and it no longer works. It is purely ornamental. I have kept it safe, pulled it out of an old storage box and displayed it in the living room. It’s a reminder of the person or persons, long gone, who held this watch and organised their days with its help. The watch has lived on longer than those people, but in a way, it’s also a dead watch. It doesn’t perform anymore. And that, too, is part of its beauty and a lovely element to reflect on.

The books

I love old books. They hold on to knowledge for ages and ages and yet they are also so fragile. The paper, so thin, so ephemeral. And by virtue of that, the words and knowledge they hold, also ephemeral.

The skull candle

I bought the skull candle to accompany me on a previous joyful death writing programme. I’d light it each morning as I read Meditations and journalled.

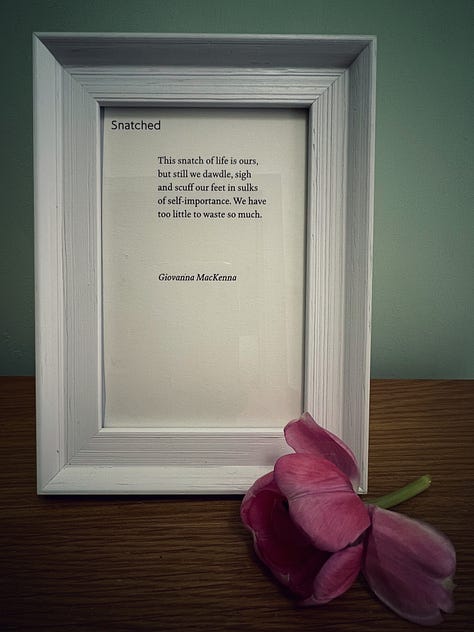

The poem

I framed this poem and shared it before we began the 7 Days of Joyful Death Writing. You can view it here. I love the expression “this snatch of life”, reminding me how violently quick this life is and yet we dawdle through it, wasting it.

The wilting peonies

I love buying a fresh bunch of flowers and noticing how quickly or slowly they decay. I will replenish and freshen their water source. I will add food sachets to make them last as long as they can. I will move them to cooler locations in the cottage when I am not actively in the room with them. At supermarkets, days-old bunches are sold at a discounted price. I sometimes purchase these almost-dead bunches as an exercise. It doesn’t matter how long they will last, so long as I notice them, pay attention to them in the present moment.

And, in the way that serendipity surprises, this poem3 appeared on my Substack feed today:

Peonies Jim Harrison The peonies, too heavy with their beauty, slump to the ground. I had hoped they would live forever but ever so slowly day by day they’re becoming the soil of their birth with a faint tang of deliquescence around them. Next June they’ll somehow remember to come alive again, a little trick we have or have not learned.

3. Sketching possibilities

Having studied the vanitas examples and collected my objects, I spent some time sketching them individually, writing about them, and sketching possible arrangements. I found that spending time sketching each object individually and then in relation to others, enhanced the contemplative nature of this exercise. I tried to resist the urge to speed up and finish this exercise.

4. Arranging the elements

I wanted to choose a space that I pass numerous times a day, so that I am reminded throughout the day. Originally, I thought I would create the still life on the window sill half way up the staircase. It’s often the first thing and the last thing I see each day as I walk up to bed at night and down from bed in the morning. It is where I currently have the skull candle sitting on a stack of Nick Cave books.

But then I bought a old wooden chest of drawers which I placed in the entry way to the cottage. And I freshly painted the wall there. I decided I would experiment with creating the still life there.

I love the aged wooden surface of this chest of drawers. I cleared the top and spent time arranging the objects in various ways. I removed items, seeking a lighter, simpler arrangement.

5. Lighting considerations

I arranged the objects in the early afternoon on a rare sunny day in Scotland. I wanted this scene to be lighter than the traditionally darker vanitas scenes. I pulled aside the curtains at the nearby window to allow light to stream into the hallway and the arrangement. This created a muted shadow behind the vase. That was pleasing.

6. Execution and capture

Once arranged, I took a photograph. I then enhanced the shadow effect to the left of the scene and added a vintage tone in Snapseed.

7. Contemplation

Now, each time I walk past this scene, I am caught by surprise! It’s so unusual having an arrangement like this in such a domestic part of the house—the entry way! It makes me pause. I do consider death but I mostly notice how pleasing and beautiful this arrangement is. I am drawn to the aesthetics of the arrangement as well as to its message.

Final considerations and the reveal!

Creating a memento mori or vanitas still life is a reflective and philosophical practice but also a creative and aesthetic one. As you mindfully gather, consider and arrange your symbolic elements, you engage with profound questions about meaning, time and mortality.

Your finished arrangement should invite ongoing contemplation, but I think it should also invite an aesthetic response. Just as we paid attention to words and language when focusing on the Stoic meditations last week, so too should (I think!) the still life attract us aesthetically.

I found that the aesthetic and tangible nature of this exercise, freed my rational mind for a while and allowed me to feel my way around mortality and transience. This practice felt fully embodied, infinitely intelligent and emotionally resonant in a different way to the writing. Funny, because the Stoics originally thought that the mind or “ruling faculty” was located in our hearts. 💙

Meet me in the comments

I hope you enjoyed this letter. What did you think of my final arrangement? What did you think of this as a philosophical practice?

Let me know you thoughts in the comments. Also, if you do create your own memento mori / vanitas still life in a corner of your home, let me know how you did it.

If you would like to share an image, you can pop into the comments below and share a link to an image in a note or post. Alternatively, we can share images in the group chat - join below. I would love to see what emerges for you!

Memento mori is Latin for “remember you will die”. Refer to this Wikipedia article.

This is such a provocative idea for project—my old house is filled with much of these relics and family heirlooms but I hadn’t thought to arrange them in a group.